The Romance of Pop Art

ANDY WARHOL

Marilyn Monroe (Marilyn), II.24, 1967

Screenprint on Paper

36 x 36 inches

Edition of 250, signed

My husband walks in the room. I’m breastfeeding. The girls are playing. I’m watching a video essay showing images from Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol. He asks:

Why are you suddenly thinking about Pop Art?

Why indeed. A better question is: why have I not been thinking about it? True, Pop Art as a subject in art history hasn’t been on my radar much in the last fifteen years. At least not since leaving school. I must have tossed it away like so much product packaging, or changed the channel on it as I searched for something more deep, more serious to dwell on. And yet, I realize at this moment that I am like a fish in water, so surrounded am I with the raw material of Pop Art. It’s all so close to home in fact, that it takes a little bit of backing away to recognize how ubiquitous it is. Themes of nostalgia, trivia about movie stars and musicians, commercials, radio jingles, old Disney animations pump invisibly through my brain along with the oxygen in my blood. I don’t love pop culture—except that I do. Somehow, it’s important to me. And that’s what Pop Art is about. Like so many childhood memories, the poignancy of an empty package, what’s here today is gone tomorrow—there’s a wistfulness there. A longing.

Pop Art Is not new anymore. At this point in time, there are objects labeled as “Pop Art” that are made with such lack of consideration that they are even MORE banal and depressing than the original advertisements and fashion images they were derived from. “How to make Pop Art in 5 simple steps” is a title of more than one YouTube video I’ve come across. I suppose a truly clever artist could make something out of that, and probably should. But Pop Art done right? Well, this is a whole different animal.

In my view, the genius of Pop Art is its sincerity. It’s in some ways a visual corollary to Punk Rock and it's more sophisticated, amiable child: New Wave. Listen to the lyrics of “The Passenger” by Iggy Pop. Or “Pop Goes the World' by Men Without Hats. I mean, what are we talking about here? Pop Art’s themes are both a celebration and a subtle lamentation of the conditions of modern life. In some cases, its urbanity and glossiness is intentionally superficial. See Lichtenstein’s ‘Happy Tears’ from 1964. At other times, as in the case of Punk music, the original glossiness of an image is intentionally marred by violence or imperfection, as if it were a rebellion against the oppressive unreality of reproduction. See Andy Warhol's portraits of famous women. In any case, Pop Art is obsessed with the reality of the surroundings, when, in fact, the artist is surrounded by consumer culture.

Pop Art exalts images that can unite us in a shared experience, while at the same time, often reminds us of our own spiritual poverty and isolation. One might ask: isn't it sad that pop culture is all that is left to bring us together as a nation? Or isn't it a happy thing, that we all know the tune to “Someday My Prince Will Come?” And that we know every possible iteration of Marilyn Monroe’s face, without actually knowing the woman at all. Unsettling, perhaps. Yet, we take our comfort.

Last night, after the kids were in bed, I tucked into a bowl of low-carb ice cream and watched about 30 minutes of “Relaxing TV Commercials from 1987.” It really was relaxing. And also a bit poignant after a while. Eventually I had to turn it off.

But then…what dreams may come.

And in a dream once, back in about 2005, I found myself in a concrete prison cell, face to face with a gastly, wraith-like figure. He came toward me with an anguished expression. I realized then that the emaciated, skull-face was that of Michael Jackson, a beloved childhood icon. “Michael, please...please help me,” he moaned. I was horrified.

I glanced over to my left and spied a narrow, horizontal window cut into the cement wall of the cell. I could then see comicbook-like images of paparazzi men, peering through the bars. At first they seemed to be trying to take pictures of Michael, but as I watched in horror, the cameras transformed into instruments of torture, their lenses emitting gruesome spikes and razor sharp blades. The faces of the paparazzi twisted into demonic grins. I knew it was a matter of moments before the demons found a way to move through the bars and into the cell, determined to further torment this pitiful soul.

Looking again at the emaciated face and sunken eyes, barely living, I was awash with pity. Just then, a mysterious open door appeared on the right hand side wall of the cell. I knew I had to act fast.

“Michael,” I said, “I can't stay here with you anymore. I am going to go through that door now. You can come with me if you want. Please, come with me. But I can’t stay here. I can’t help you here. I can’t.”

But the poor creature was insensible to my words. So, forbidden to wait any longer, I turned and ran through the door and out of the cell, leaving him behind with his torments.

I know some of you may laugh at that image. But for me, the dreamer, it was deeply troubling. That’s why I remember it so well. Was it a prophetic dream? With the amount of time I’d spent as a child, wishing Michael Jackson would walk through my bedroom door at night, and be my friend, perhaps I forged some kind of unexplainable psychic bond with him. Perhaps he was crying out to his fans for help, isolated in his own personal hell of fame and infamy; driven insane, perhaps, by his own self image, which he neither owned nor could control, reflected infinitely by the disco ball of the media, a childhood joy-ride that had become a nightmare carnival for him as an adult. The King of Pop. And one of its most wretched casualties.

And perhaps Michael was me—Michael. Maybe this other me inside myself had appeared to warn me of a dire fate, as all classical wraiths do. Perhaps I was unconsciously preparing myself to walk out of the self-made prison of addiction, leaving the vain, starving, hungry-ghost version of myself behind. I got sober later that year.

Fast forward to the real world. The world of watchfulness, of early bedtimes, of sleep without screens. Let me remember what it is that I can do to find comfort, even strength amid the overwhelming THING-ness of life. Like Ebineezer Scrooge at the sight of his own grave, now I pray.

But that’s no easy fix. Because of my brain and my experiences, I am often forced to confront even God as a cheap holy card, a glossy print, another dubious image, a product of popular culture. When I try to pray, ‘Pop Jesus’ can get in the way. Sometimes it’s excruciating. Like trying to accurately remember the face of a loved one who is long dead. At moments like this, the profound lament of Andre Serrano’s “Piss Christ' appears dimly in the background, like a weeping angel. Breaking through that wall of “fake” often feels impossible, though I remain. And God willing, I will remain. And then, sometimes, a mysterious door opens up, and I am permitted to pass through into the bright morning sunshine.

Yes, there is something better out there than psychic trash, the raw material we constantly ingest, like so much microplastic, in this crinkly, warmed over Dasani water bottle of life. And that’s what the best of Pop Art is hinting at; that there is something better. But you have to look at it, in order to see through it.

As an artist, I often attempt the short cut, and try to cut it all away. All the trash. Replace piles of printed pablum with one simple image: the face of The Beautiful Lady. No, not Marilyn Monroe—the other one. The Original. And wasn’t that what Warhol did, too, when he went to shrive himself every Sunday, by going to holy mass with his mother?

The junk and accretions of this world accumulate, and we have to scrape them off from time to time, or we sink. But sometimes, we need to save a few special artifacts too, because these are the things of our lives. We cannot be puritans, afraid of decorations, afraid of images. We were made of flesh, and with brains and memories. We have to look at it, in order to see through it. And God so loved the world.

Looking at Pictures Again

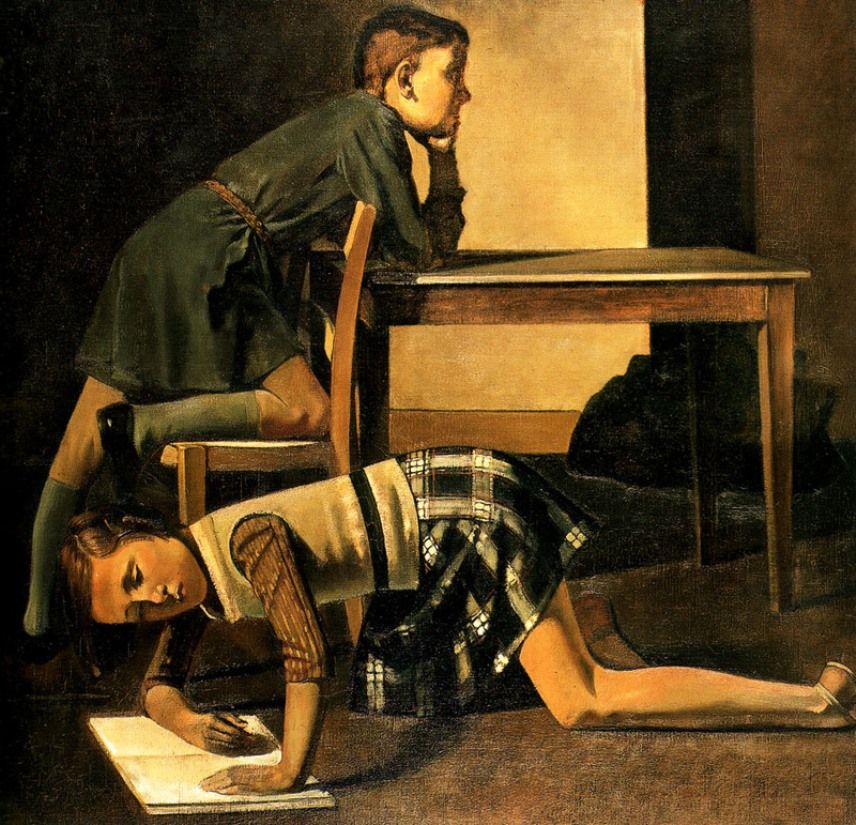

There was a time in which I was a little girl, frozen still on the floor, gazing into a book at a painting by Balthus.

I’ve gone through periods of life where I almost became “tired” of art. Weary of it. A bit nauseated thinking of it in the way that I’d grown accustomed to: as a professional in which I felt like a success or a failure by turns. It had become hard not to ruminate about the political or social controversies in the industry that have nothing to do with art, really, but had somehow eclipsed the original joy of making; of looking at pictures.

I used to sit in my room on the floor as a kid with a big coffee table book of painting on my lap and just look: and look and look. I could barely understand the language of the captions so that didn’t impact my thinking too much. I saw names and dates, a few words here an there I recognized, but I knew so little of history and the world that it told me almost nothing. All I really had were my eyes and my open, flexible, responsive mind. I would look and follow the lines and shapes and colors and forms and simply take pleasure in them.

I knew the paintings meant something. The full story I tried to guess, but being a little girl I couldn’t quite make it out. Yet there was the delectability of a limb, the blueness of a cast shadow in sunlight, the gaze of a silent face, distorted by the ineffable choices of the painter, moves that some how took away everyday reality, and turned mundane details into poetry. It was a silent poetry I was listening to, with my juvenile eyes and mind.

I’m only just beginning to come back to that original pleasure of looking. I’m losing my weariness and my wariness of art. The word itself is beginning to signify hope again. I know it’s something good, one of the great goods of life. And it’s something I am now becoming free to enjoy again, without having to wonder how I measure up, or how I can do better as a professional. Taking art works as gifts, and not always as instruction manuals in technique, or goads for my own ambitions as a painter, but simply as wonders to be enjoyed for themselves, is a quiet renaissance for me. I am grateful for it.

Seeing Stella

On the beach today again, with the girls. Their little bodies are such a wonder to me. The light was raking across the water near sunset. They were taking turns climbing up a driftwood log, and jumping down. “Mommy!” My eldest daughter, Stellamaris, kept shouting. “Look at me! Mommy! Look!” I was drawing her, of course. Technically, I was looking, looking right at her, but not in the way she wanted.

I was in fact, looking at the way her silhouette appeared almost black against the absolute brilliance of the sun reflecting off the distant water. The water was transformed into this kind of sustained lightening, like the face of an angel, almost blinding. And Stella’s shapely little legs were outlined by this glow. I was attempting to make a note of it in charcoal, but it seemed impossible to reproduce the impression. If it had been photography, I’m not sure that the camera lens would have done a much better job. Of course thinking about what a camera would do with a situation like this, was helpful in imagining an approach to recreating the atmosphere. With confidence, I drew my brilliant little pale skinned daughter as a pitch black figure of uncertain parameters, knowing from experience of looking at photographs that only the highest possible contrast would invoke the brilliance of that surrounding light.

And the thought occurred to me: this is why ‘The Impressionists,’ but not just them--everyone who painted and drew from around 1870 onward began to do crazy things like make their figures look black in the sunlight, let murky blue shadows tear across the integrity of a lovely face so as to flatten it; to disfigure a body in the same manner--because this is the closest thing to they could get to capturing certain optical effects with tones of pigment. And they were acutely aware of these effects because everyone now had begun to look at photographs. The cat was out of the back. The camera really did cause this visual revolution in art. New boldness came from new visual experiences, mediated by light, and strangely, by technology.

To all my fellow sighing moralists who would love to turn back the clock on modernity to the point of excluding modern and postmodern visual art and its unruly, crude and rash innovations, reductions and experiments, I’m afraid it's too late. You, too, have seen photographs. Your brain is full of them; formed by them. You, by virtue of having lived and learned in this world, have a modern mind and a modern eye, whether you like it or not.

To the machine-minded workmen; the get-it-done engineers looking for pat answers and quick fixes and formulae for art: there's your answer, right? Problems of drawing and painting solved now and forever: just get yourself to imitate a camera lens and you now have all possible knowledge of what it takes to make a likeness, and therefore, a picture. A work of art. But is that all? Certainly not! The camera, whether it be the cool, metallic machine or the flesh and blood eye, is neither the beginning, nor the end of art. Even visual art transcends these material parameters, if you believe in art as a spiritual good, and I do. Setting aside the delicious questions of craft, materials, subject and technique, all of which are a great deal of what painting and drawing is about, there is so much complexity in the phenomenon of seeing that an artist can (and usually does) spend a whole lifetime muddling through it.

In the end it's like grasping at so much straw. Tantalizing, dazzling, majestic, fugitive straw. One moment on the beach brought an overwhelming complexity of shifting contingencies, of changing relationships. My daughter was only a ‘black phantom’ for a split second, then the tonal values changed again and she was a ‘brilliant angel,’ and back again, and so on. The light source was gradually changing all the while as I chased the gesture of her dynamic little figure with my charcoal. As the given shape changed, the perspective changed constantly too, and not only that, my focus kept changing: first looking here and then there, squinting, adjusting, my irises opening and closing against the brilliant light.

And then there’s memory; what I already know about her figure; what I’ve already experienced of being in these kinds of situations; what I’ve recently learned about the shape of my current surroundings, the scale and distance and potential of objects all around me; unfathomable complexity that my mind and eye are somehow pulling together at an amazing speed to deliver to me a visual theory of reality that is consistent and reasonable and plausible; a synthesis of a countless number of mental “photographs,” combined with conceptual images, maps and unconscious schema learned from countless millions of moments of living and perceiving objects in this world.

And then there's even more sensory information: my sense of touch; my haptic sense whispering to me of the physical presence of things. The senses, maps and memories yield fugitive impressions, but they come together to make a whole, a gestalt, and that’s what the artist is trying to capture, for a start. But then, there is meaning. The meaning of this dancing, flickering angel before me; her countenance alternating between dark and light…my daughter, Stellamaris…four years ago her body came out of my body…flesh of my flesh…I sense the dull ache between my legs as the memory of birth brings phantom pangs…where did she come from? Where will she go? And I’m just drawing...drawing on the beach.

“Mommy!” My daughter kept shouting. “Look at me! Mommy! Look!” Technically I was looking, looking right at her, but not in the way she wanted. Perhaps I should stop for now.

Stella Maris, Star of the Sea, pray for us!

LIFE: Metamorphosis: 2016-2020

Today, I did something I’ve been contemplating for quite a while: I deleted my Facebook account. Permanently. Poof. Gone. There are many reasons for this and I may discuss them in a future post. Suffice it to say that I must conserve my time. This is partly what enables me to turn my attention again to this website, and upload fresh art and content here, with a focus on art, faith and the mysteries of family life, going forward.

It’s been an eventful four years. Here is what I did since I last updated this site: found myself painting my first ever nautical-portrait for a pretty accomplished local art collector bobbing along in the Puget Sound; took on a commission to paint ‘The Stations of The Cross’ in fifteen installments (more on that later); traveled to Europe; got engaged; lost thirty pounds; planned my own wedding (this was more challenging than childbirth); got married; traveled to Europe again (makes sense, since I married a European); got pregnant; took several birth classes and studied a library on natural childbirth in order to allay my anxiety; gained forty pounds and transformed into something resembling a watermelon stuffed into a suasage-casing; temporarily ceased all painting out of a disproportionate dread of poisoning my developing baby with toxins; gave birth (in the hospital with some difficulty); recovered slowly while figuring out how to nurse a newborn and be married and be a mother at age thirty six; got the hang of it; lost some of the pregnancy weight; resumed painting and teaching (for about five minutes); got pregnant again (by then my body resembled a leather bag, deflated and then re-inflated again like a wine-skin); traveled to Europe (this time, with an infant); flew to Tucson to look for houses (then found out we would stay in Seattle for the time being); experimented with decoupage; interviewed every homebirth midwife in town and finally hired one; moved out of married student housing (my husband finished his PhD); gave birth to my second baby (in the height of the pandemic in the basement of our hastily rented house, with great wonderment); made the decision, with my husband, to leave my beloved Dominican Catholic parish of ten years to join a parish that offers mass in the Traditional Latin Rite (there may be more on this later); learned how to be a mother of two children under two; started drawing again to keep my hand in it, and found my children to be a fascinating new subject, as long as I give up total control;

and now...

More recent work will be uploaded soon. I promise. Having children has changed everything. Parents will attest to this. Everything I do now takes double the time. Most things are done with my one free hand. Like typing this sentence. Constant interruptions are a way of life now. Gone are the days of dissapearing into my studio for hours or days at a stretch, brooding over ideas, anticipating the start of work, obsessive focus excluding all else until the work is complete. Things are accomplished now, if at all, in five minute spurts. They have to be. Time has become a precious thing that I do not own. I’d tell you more about how this has changed the some of the qualities of my work, but just now, I am compelled to nurse the baby down.

The Catch

He has a penchant for juxtapositions. The grey Pacific Northwest winter months culminated, as they do every year, in the gentle severities of Lent: fasting, abstinence from meats and sweets, kneeling and praying the Stations, meditating on the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary and so on. During this time of solidarity with the Sufferings of Christ, my professional task was, nonetheless, to produce the brightest, sunniest, dare I say: ‘happiest’ painting I have ever yet attempted. This irony made me smile, for though the daily effort to face skies of cerulean blue and clouds of titanium white amidst an atmosphere of somber introspection was a cross in itself, the work was sweet, and I was grateful for the commission which would put gas in my car and pay the rent through the winter.

If I had to write a book entitled ‘The Boat’ it would be filled to the brim with dubious treasures. Gold disguising lead disguising gold--shapes covered with slime revealing living things that look and smell bizarre but are true delicacy to the mouth and sustenance to the body, would issue from such an excavation. Things that really happened and things that didn’t quite happen would all come tumbling out haphazardly, poorly rendered and linked together by chance, all in an elevated tone as if they were really the thoughts of someone very important and wise.

‘The Boat’ as I have come to think of it, is a physical blessing that brings with it many subtle graces; gentle enrichments of soul, something of which I will attempt to sketch out here in the particular case of a commissioned painting. There are too many facets and layers to describe all or even most of this one tiny piece of anatomy. A painter well knows that life has what you might call a “Power of Ten” quality; one can zoom in or out, ad infinitum, and keep unfolding worlds. It’s really too much for human beings. Angels of supreme intelligence can just barely stay abreast of the unfolding. Yet I must at least hint at the existence these precious nourishments, so as not to waste anything that might be divided up and shared among friends. If The Boat is too much, let me at least convey one small pearl that issues from her nets, namely, ‘The Catch.’

The Catch was a surprise that began with the 800th anniversary of the Dominican Order. Having a special affinity for St. Dominic and many of the saints that followed his example, not the least of which is Blessed Fra Angelico, ‘The Angelic Painter,’ I saw here an occasion to do something big. I had in mind a large scale portrait of St. Dominic for the Church. I asked the Saint to intercede for me in this matter, if he wouldn’t mind. I admit I was so bold as to mention specifics, including the price I needed in compensation for the work.

I thought of the fiery intensity of El Greco’s St. Dominic. Looking at a reproduction in one of my old books, an ember of desire smoldered within me. I wanted El Greco to teach me of painting and of devotion too. If it came to be, the painting would be a true effort of love. All we needed was a sponsor. Surely some benevolent patron could be found to support such a timely tribute. I resolved to show up at a gathering at our Dominican parish on the very next Saturday to celebrate the start of the Jubilee Year, and perhaps find some willing client to fund the project.

Soon after, Krzys sent me a message. It just so happened at the same time that a young friend of ours was about to embark on a period of discernment with the Dominicans in California. His family was having a little get together to celebrate his going away. It was also on the very next Saturday. I considered what St. Dominic would have me do. Though I sensed my original plan was a good one (and I very much needed a commission), it seemed to me that it would please St. Dominic more to encourage a young man who might join his order and become a holy priest. I gathered his non-Catholic family was rather perplexed by his interest in the priesthood, all the more reason to encourage him. So Krzys and I journeyed to grandpa’s beach house in Bremerton.

I was expecting a hot-dog and shorts affair. Imagine my surprise when I arrived at Grandpa’s elegant home to realize that the man was a consummate collector of modern art! The beach-side property was packed with specimens. I remember more than one large scale Frank Stella and several huge outdoor modern sculptures. The place felt more like a museum than a beach-house, even more so in the otherwise blue-collar town of Bremerton.

We hit it off swell, of course. I think grandpa Paul enjoyed talking with someone who understood something about his little ‘hobby.’ He toured me through the collection with joy, and regaled me with stories of his buying and selling escapades. He told me he had for several years owned a print of the famous / infamous “P*ss Chr*st” by Andres Serrano but had finally sold it if (at three times the original price of course) in deference to his father, who hated it. I began to get the picture. The fact that I knew Serrano’s work and could comment intelligently on it without rushing into whether or not it constitutes a sacrilege opened up a doorway of trust between us. 1

It was at that point he asked who is “representing” me. I responded quickly that I am “self-representing.” With a twinkle in his eye that told me he sensed a bargain coming on, he asked me to follow him. He lead me to his office and showed me a large photograph of a sail boat racing along near a rural bay, surrounded by blue water, big sky and a rolling mass of clouds. “Do you know anyone who can make a painting out of this?”

When it came time to set the price, I remembered my earlier prayer to St. Dominic, and faithfully quoted the amount I had asked the Saint to dispense for my next piece. With gratitude, Krzys and I drove off with the oversized photograph (a journalistic image of Grandpa as a young man with his crew in his boat winning the historic Victoria to Maui race in 1976) in the back of my car.

We took a ferry to visit my dad on Vashon island to celebrate and to rest. The late August light drizzled the arms of the trees with honey; the water of the sound, cool and black as obsidian mirrored back their golen limbs. As the three of us sat in the little motorboat some fifty feet off the shore with our lines in the water, we reflected on the generosity of God to provide what we humbly ask for (and need), especially through the intercession of his Saints. This is most true when we relinquish our own assumptions and allow our Father to direct us in his ways, to put out our nets whenever and wherever he tells us.

I was beyond satisfied, yet I still couldn’t quite see why St. Dominic would have me paint a group of hopeful young men on a boat winning a race to honour him and his brother preachers. I was musing over this question when suddenly came that telltale ‘buzz’ on one of the lines. To our shock, we pulled up, as if by magic, a large, silvery King Salmon out of the deep.

My dad used to take me out fishing some when I was a little girl. It was one of our favorite pastimes together. It had been a while. Dad is of the age now where every special experience between us has the quality of eternity. We share a golden, grinning awareness that this could very well be the last time.

I manned the net. Krzys was thrilled; he had never ever fished before. Dad was speechless--he really had no intention of catching anything. He used only a rubber jig; intended merely to spend a little time demonstrating the technique to us and to have a peaceful boat-ride. It was like a prayer offered lazily, half in disbelief, answered at once.

There was some misgiving about whether to keep the fish or throw her back, but the hook had done its work and she was already giving up her life. We motored home, cutting a path through the glassy blue in silence. Dad solemnly butchered the animal, unwilling to let any of the unmerited gift of the Salmon go to waste.

My own grandfather, Virgil, whom I hope to finally meet at the hour of my death, is a Boat-man; an honourable Navy-man of modest rank. I say ‘is’ because I trust he is alive in heaven. A quiet convert to Catholicism, he had been raised sometime on the Reservation. By all accounts, Virgil was a saint on earth who kept his thoughts close to nature and close to his own heart. Whenever I see Dad cast into the deep of his father’s memory for the simple know-how which eludes most men today such as: ‘how to catch and clean a fish,’ or ‘how to bury the dead,’ his usual effusiveness is quickly subsumed into the silent, intractable wisdom of Virgil. This was how it was as we cleaned the fish.

Opening her belly revealed a trove of caviar glistening like rubies in the sunlight. These were for me. I examined them, holding them up to the light. I cleaned and salted them carefully, and ate every single one over the next several days before I began to plan the painting which was to be my food for the winter, reflecting on the Providence of God, the boat, the water, the faith, the fatherhood, the sacrifice, life and death; everything.

Anyway, it was a good catch.

And now, since Lent is over and gone with ‘The Boat’ (actually, the official title of said painting was ‘The Race,’ but that’s another allusion), Easter time is here, the spring is with us, the air is balmy and fragrant with lilacs, I begin my next commision: the dolorous narrative or our Lord’s suffering and death, or “The Stations of the Cross.” As I said, he has a penchant for juxtapositions.

____________________________________________________________________________

1The piece is objectively sacrilegious, though I am not sure Serrano was fully conscious of that when he made the work. In one interview he claims to be ‘a Christian,’ yet one wonders in what sense he uses the term. If it is true at all, he clearly lacks the formation to understand the effects of his actions, which mitigates some of his culpability. This maneuver may deflect some of the heat from a moral standpoint, but a strike against him as an artist. Serrano claims to be ‘experimenting’ on the public with his concoctions, though he is ignorant of the results or doesn’t choose to think about them. I doubt that Serrano conducts his work with malicious intent, but he lacks intellectual integrity. I do understand the fascination of Serrano’s imagery, including “P*ss Chr*st” yet, reason forbids me in conscience to celebrate it or to freely pronounce or write the offensive title.

National Portfolio Day: The Power of 'Schlepping'

I have a personal story to tell about National Portfolio Day. I've naver shared it before, but it is important to me, and every January, it comes back to my mind. For those who don't know, NPD is a sort of European-rules college fair for young artists seeking to get into a competitive art-school track, hoping eventually attain the mystery of the coveted, yet elusive, parentally-misunderstood and generally terrifying: 'career in the arts.'

I remember when the event was held at the Seattle Center, back when I was just a sophomore in high school. A family friend, April Ferry, a beloved and now-retired art instructor at the Seattle Academy of Arts and Sciences (SAAS), encouraged me to go. I was not a student of SAAS. I really had no art program in the Catholic school I attended. But being a neighbor and a kindly soul, April did what she could to guide me. She gave me a lot of good advice and encouragement along the way without which I might never have found my footing. Having been a New York art student and a working artist herself, she taught me the meaning of the word 'schlep.'

And schlep, we did. All my stuff--goopy canvases, dusty drawings, greasy sketchbooks--up the steps inside the Center House to wait, terrified, in the long cue for a chance to have my work reviewed by actual representatives of some of the finest art colleges and academies in the country. This was in the days before digital photography, long before Tablets and IPads. We had to schlep our stuff in the flesh. And it was worth it.

Those brief conversations with the 'Reps'--actual artists themselves, people who seemed to care so much and take a real interest--changed my life. These people understood something about me that hardly anyone in my life could understand: I too, am an artist. The Reps could see it and they took me seriously. They spoke confidence into me; they told me I really could have a future in this. Even more, they affirmed that what I was doing with my time was something, well wonderful. I came away from my first National Portfolio Day with my heart blazing with hope and my work cut out for me.

The following year, I was a junior, almost ready to make my college applications, and I was well prepared. I had assembled the best of my work and had worked hard with whatever instruction I could find outside of school. I was doing figure-drawing from life at local art stores and anywhere I could get in front of a live model. I was taking workshops and visiting the studios of local artists, asking them questions. I was working with oils. I was reading practical books and art history books. I was copying artistic anatomy, and devouring reproductions of the works of my chosen masters.

That Friday night in January, I had my glossy black portfolio-brief all full of drawings, with my best canvases bundled up beside it. I went to bed early enough to get up on time. I wanted to get the full day of glorious critical feedback and insight, a chance at scholarship money--maybe even a rare 'on-the-spot' acceptance from some great, prestigious east-coast school.

When I awoke, it was still dark. Dad was shaking my shoulder, telling me the news: last night, someone very close to me, a friend and a mother, someone who was an intimate part of my childhood, had died. The body was found this morning. I'd better get dressed and come quickly. It was the worst day of my life.

Many hours later, after the police and the coroner had gone, and sobbing had dwindled down to a dull murmur in the house, dad took me aside and asked if I still wanted to go through with it. He wanted to know if I felt willing to take my work to downtown to National Portfolio Day to be assessed by the visiting colleges. If we hurried, there might still be a chance to have my work reviewed. Could I handle it?

I didn't know. I looked at my paintings and drawings all bundled up and ready. I had worked so hard for this moment. This was my last chance to be reviewed before I made my applications. I felt that some Reps had the power to make me an offer of acceptence, and that would seriously impact my chances of success as an artist. I thought of the future I longed for so much, and weighed it against the grief and weariness and agony of the day.

We schlepped.

I wasn't nervous standing in the line this time. I was numb. I had just enough time to speak with one or two representatives before the horn sounded and National Portfolio Day was officially over. I remember looking down at the table where my portfolio was laid out for inspection. I was now older than most of the other kids. I could see that my work was excellent, in some ways, very advanced compared to the others. I should have been proud, but I just couldn't care that day. I was too sad to feel anything like pride. Yet I stood in those lines at National Portfolio Day, clutching my work.

When it was finally my turn, I set my canvases on the table. There was my latest self-portrait in oil, the eyes, life-like yet weary from staring into the mirror, gazed up at me from the table. Then came the dread moment: as the Rep worked her way through the pile of canvases she finally pulled up an oil-portrait of the very person whose death had changed my life that day.

The Rep kept talking to me about my painting, but I couldn't focus on what she was saying. She sounded far away. I heard her voice suddenly grow concerned as my eyes began to fill with tears. I couldn't look up. I just kept staring at those eyes in the paint, burying myself in them until the critique was finally over.

Dad helped me get my work back to the car and load it up. Wearily, he turned on the engine.

"Come on, let's go back to grief street," he said.

I am an artist. I proved as much to myself that on that dreadful day. I had never been touched by the indifferent force, the shock of death before. My sense of everything, the world and myself, changed forever.

Nothing felt okay, yet I watched myself do what I had set out to do anyway. I was reeling, terrified, but somehow I held on, for my self, my work, my future, because it was the only thing I could do, because I am an artist. In the midst of intense pain, I carried my work, my heart, my whole internal universe in a heavy bundle and laid it out before the eyes of objective scrutiny. In a way I still don't fully understand, this decision set up a spiritual foundation for who I am today. I schlepped.

There were no scholarships offered, no 'on-the-spot' acceptances that day. Due to financial constraint, my parents could not support my dream of going to a school on the east coast after all. Yet the dye had been cast. I had made my decision.

Months later, I received notice of acceptance to the University of Washington. On the first day of fall quarter at the state school, I marched across campus to the counseling office to declare my major. The counselor looked at me incredulously.

"Most students take at least a year or two before they're ready to declare a major. Your classes haven't even even started yet. And students usually change their mind, several times even, as they work through their general education requirements. Plus, you won't even be able to enroll for painting classes for the first two years. Are you sure you want to declare your major today?"

"Yes," I shot back. "My major is Painting. I wish to declare Painting as my major. Go ahead and write it down. Painting. I won't be changing my mind."

And I haven't.

So that's my secret story about National Portfolio Day. Now, as fate would have it, almost two decades later, I find myself appearing there in January, this time on the other side of the table--at the end of the long lines of nervous teens gripping their portfolios--as a Rep.

I don't normally tell this story of my experience with the event, except to say that I attended it faithfully it myself when I was in high school, and that it was indeed life-changing for me. However, I never can stand behind that seemingly mile-high table, scrutinizing the dreams and longings of hopeful students, sometimes pathetic, sometimes humbling, without remembering what it really means to me, and what power there may be for them too, in schlepping.

On Being a Woman Painter or 'Fake Blood'

If only beauty were enough,

if desire were currency,

I could sweat the toil of my trade,

and trade the products of longing for a life.

A lifetime of time and being would be born

complete and viable,

projected, crimson, onto walls

Inside The White Cube of reason;

begetting little cubes.

Viscera would be cordoned-off and labeled

in Times New Roman,

while unflinching Prudence

pushes pins in,

centers, justifies, edges, frames,

binds blind organisms, birthed--conceived,

in fervid dreams,

with Philosophy's cool surname,

and hands

dollars over fists

to clench it,

make it alright,

set it aright

with right angles.

I would spend every night

and waking day

making this kind of life.

I’d never paint a Crucifixion without tears rolling,

as in Fra Angelico’s face

of Christ, inviolate, radiant with restraint,

deep in his science.

I’d never work without a prayer to make

cadmium drip from my eyes

onto skins, titanium;

bones beneath them, white;

transparent tissues scumbled over yellow fats;

blood vessels threaded like roots,

blue through the zinc,

and umber hairs that shoot

from delicate membranes,

laced with lead,

and places where the white turns red

with feeling

(parasympathetic response),

always just turning red

(rose madder lake),

in perpetuity.

It would be enough for me.

And for beauty alone,

I would live until it was time to die;

fake blood,

love, work,

and never worry

about such moot questions as

‘where are my children?’

Where, my Spouse?’

Land-Escapes

Looking at the landscapes of George Inness, and a few other tonalist painters from the 19th century, I am drawn in by the lure of the blacks. Deep, rich, throbbing, cosmic blacks. They remind me of the blacks of the shadows of Van Eyck, and other flemish masters. Blacks that defy reason, and yet have the effect, among other things, of bringing certain forms of the composition into full disclosure. Rendering them so pointedly clear as to be somewhat ominous. I have yearned for these.

Yes, I have longed for these blacks, and also, I have been harboring a desire to paint my surroundings, to apply myself to landscape study in earnest after so many years of focusing almost exclusively on figure. Recently, I went so far as to mention, in response to a question about my work, that “I also do landscapes”--which is stretching the truth I would say, since the last thing I did that could really be called ‘landscape’ were some thumbnail watercolors back in 2010, and before that, a single class taken with Philip Govedare as an undergraduate. What could have possessed me?

Thus, starting from last weekend in the midst of a most welcome rain storm (or what felt like a storm after so many weeks of uncharacteristic drought), I have found myself furiously gessoing small panels and boards in an effort to make this taste of black-in-landscape come to me as quickly as possible, and without further study or conjecture about how in the heck one is supposed to go about making good landscape. Oh yes, I have to admit I have been less concerned with perfecting the ground than one should be, too; I am acting a bit of a glutton. But what do I care? These sticky little rectangles are falling (and failing) from my easel like so many hastily opened chocolate bars, half finished and flung even as I move to gorge myself on the next. Yes, I am a glutton these days! It’s no wonder each session has left me feeling a little empty, and somewhat embarrassed of how little I have accomplished thus far. When will this binge end? Perhaps when my understanding catches up to my urge to attack my surroundings with paint. Am I painting angry? Perhaps. The only thing for it is to paint more.

I am learning my way. Today, it came clear that the way to handle these curtains of trees upon trees, especially evergreens near the water in the summertime, is to start the thing with a base tone of blue. Then the blacks can be added--not washed in, but hatched--to make form, like building the fur of an animal that extends from the taut and muscular frame underneath. Thousands of little terriers.

Yes, my mind is brewing with a black and sticky logic, not too well defined but searching dutifully, and a bit frantic. Like household chores blurrily undertaken in a concerted effort to stave off sadness, this is the particular moment of my art. When it passes, I hope I will have gained in virtue.

Some Thoughts on What it Needs Now

Northwest Catholic Magazine

It has been an honor and a privilage to have my work and life appear as the cover story of Northwest Catholic Magazine this past December. Anna Weaver and the rest of the staff at NW Catholic did an amazing job of presenting my story with both sensitivity and directness. The whole process took several interviews by phone and in person, numerous emails and recordings, as well as photo shoots and filming to produce the accompanying video. Beautiful hard copies of the magazine were distributed widely across the archdisocese, and so many people have approached me and thanked me for the story; for the candid way in which my life was presented. Some have said it deeply touched them.

I have to keep telling people that it was Anna Weaver and the people from the magazine, the editors, photographers and all who were envolved in the production and distribution of the story that really deserve the thanks. I am humbled to have been a part of this project and to have recieved such support from the Archdiocese of Seattle.

Click HERE to read the online version of the Northwest Catholic Magazine article, 'The Art of Faith.'

Enjoy the short video below!